The Beginning Violinist – book completed!

I am happy to announce that my book, The Beginning Violinist, is now complete! I am very excited to offer this material to you since it has been so helpful to me in working with my own students. This book is meant to be used in conjunction with the method books and materials you currently use to fill in the gaps left by even some of the most popular method books available on the market today.

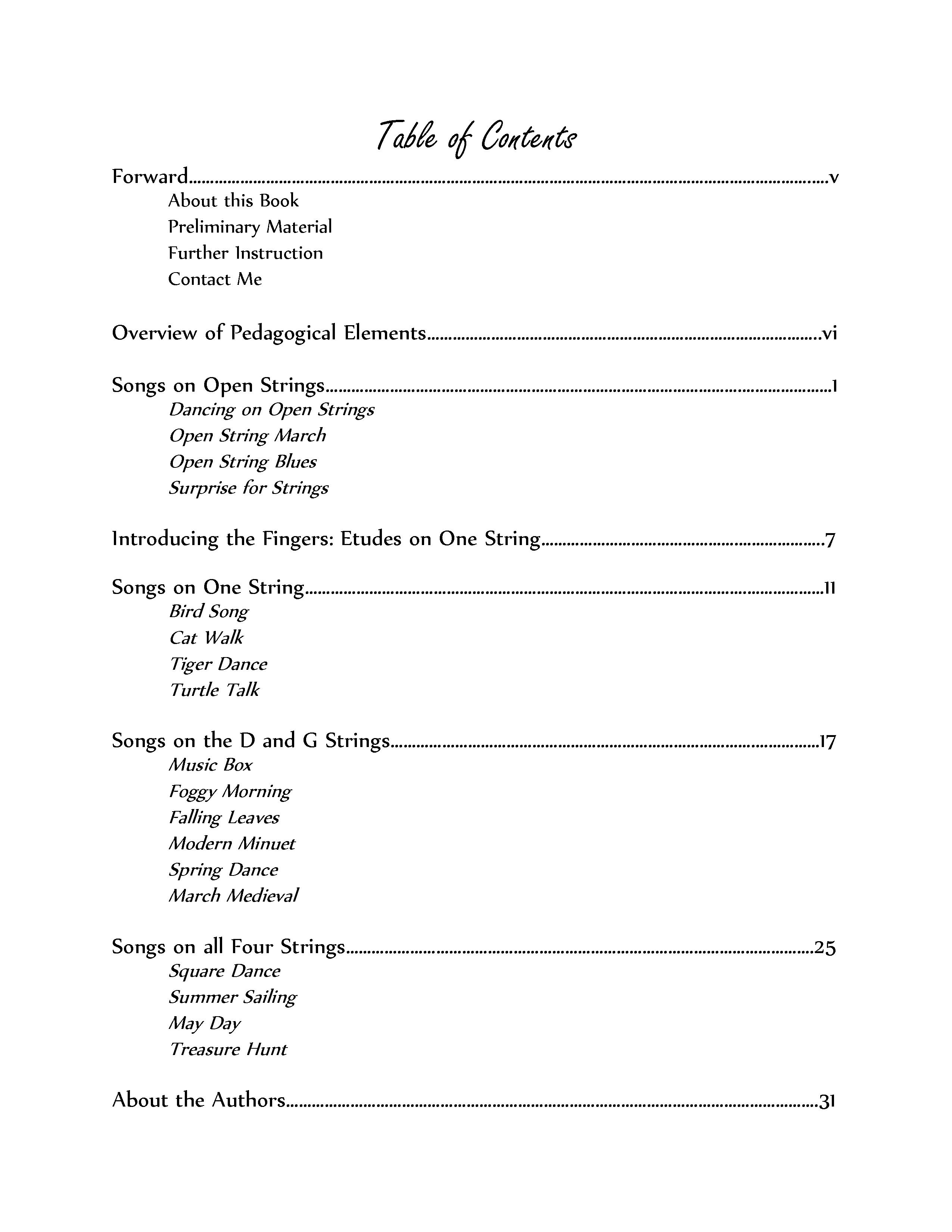

Here’s the table of contents so you can see what you’ll be getting:

If you have previously contacted me about your interest in my book you will be receiving a personal email inviting you to purchase The Beginning Violinist at a discounted price. The final retail price will be $15 (+s/h), but I am going to make it available for a limited time for $10 (+s/h) as a thank you to you all who have supported my efforts along the way. If you are interested in purchasing a copy please email me at [email protected].

If you would like additional information about The Beginning Violinist please view my previous posts about the book’s content, or contact me and I would be happy to answer any questions you may have. I look forward to hearing from you!

Emily Williams is the creator of Strategic Strings: An Online Course for Violin and Viola Teachers

New Beginning Violin Book Update

I am happy to announce that I have only ONE more song to “try out” on my students before finalizing my new book; The Beginning Violinist. I am very excited to be in these final stages and want to let you know how you can prepare your students, and share some comments from mine!

Here are the skills you can be working on with your students so that they are ready to begin the first songs in The Beginning Violinist. (I usually use rhythm and note cards to practice these concepts):

- Hold the violin correctly between their chin and shoulder

- Be able to identify the name of each open string on the staff and pluck it at sight

- Be able to tap and say quarter note and 8th note rhythms in a steady beat

Once a student can accurately and consistently perform these skills The Beginning Violinist will provide repertoire that puts these two concepts together.

I would like to share some comments from current students using the repertoire from The Beginning Violinist.

“I have enjoyed listening to my daughter play the compositions from The Beginning Violinist . She has learned three songs: Cat Walk, Bird Song, and Tiger Dance. While listening to her play, I realized she did not stumble through the songs, but quickly responded to these creative, one-string arrangements with competence and confidence. My other daughters [under a previous teacher] started out on songs that used two open strings. Comparing the different musical beginnings of my daughters, I appreciate these one-string compositions to facilitate a student’s focus on learning their notes and rhythms.

I saw my daughter enjoy listening to the sounds she produced from using Dr. Williams’ songs. Since she was working only one string within each song, she had the capability to combine her new found skill with her imagination while playing (for example, she smiled while playing Cat Walk because she could “see” what the cat was doing!).

I have seen my daughter learn notes by sight more quickly than my other daughters who had a different educational approach. [The repertoire of The Beginning Violinist] has allowed my daughter to gain the ability to blend her notes and rhythms on three strings with agility.”

~Leigh (parent)

“As an adult, absolute beginning violin student, I really appreciate learning all of the open strings of my instrument at once. I feel learning this way opened the door of available music much wider. These selections allowed me to experience the entire finger board of my instrument. The selections also provided experience in different techniques as well. I would highly recommend them to complete the beginning violin experience.”

~Nancy (adult student)

“I like the idea of teaching all open strings [to start]. I think it lays a good foundation knowing what the open strings should sound like, and also they can help later on when playing a note that is an open string note and you are trying to make sure it is in tune. I also like the idea of learning all four fingers together because it helps me learn what my hand should feel like when playing finger patterns.

I like how the pieces [in The Beginning Violinist] introduce and incorporate a lot of concepts at once. Like in March Medieval there are the accent marks, staccato, slurs, and dynamics. At first it was challenging, but when I started to get the hang of it I felt that I had really accomplished something.

I think [the songs] have contributed to my learning in the fact that I’m using more strings than just A & E and that gives me a feeling of being more competent with the instrument. When I first started lessons I considered my musicianship nonexistent. Now I feel proud of my accomplishments in my musicianship as a late learner in life.”

~Emily (college adult student)

New Beginning Violin Book

I am excited to announce that the beginning violin book that I have been working on with my husband (composer Dr. Benjamin Williams) is almost complete!

This book has been several years in the making and is meant to be a companion book to the many beginning violin method books already available on the market. If used by itself it would leave much out of the beginning violinist’s instruction, however, the need arose for this book because I believe that the majority of beginning method books currently available also leave out much of what is needed in the beginning violinist’s instruction. Therefore, coupled with current popular beginning method books, this companion book will round out the beginning violinist’s repertoire. If used under the supervision of a capable teacher this book will serve to balance the musical instruction of both the child and adult beginning violinist.

Why is such a book needed?

Problem 1: Beginning method books tend to focus on the A and E strings to the exclusion of the D and G strings.

Solution: This companion book focuses heavily on repertoire that uses the D and G strings. That is why it must be used in conjunction with more popular beginning method books. Students need to learn ALL the strings, and this book is the perfect solution.

Problem 2: Beginning method books tend to use only traditional Baroque and Classical harmonic structure.

Solution: This companion book branches out into more contemporary harmonic structures in a way that is accessible to the student and pleasing to the listener!

Problem 3: Beginning (and even intermediate) method books contain mostly pieces in one key or time signature.

Solution: This companion book introduces the beginning violinist to changing meters and keys in a way that is easy to understand and idiomatic to the violin.

Problem 4: Beginning method books tend to teach the 1st through 3rd fingers, but not the 4th finger.

Solution: This companion book teaches all four fingers right from the start in a way that helps to correctly set up the students left hand and reinforce correct technique/posture.

This is a selective example of the problems and solutions that are addressed by this companion book. All the materials in this book have been tested on my own students and proven to be useful, accessible and relative to both children and adult beginning students.

If you are interested in my material please email me at [email protected] and I would be happy to let you know when the book is completed so you can get a copy!

Emily Williams is the creator of Strategic Strings: An Online Course for Violin and Viola Teachers

Playing vs. Practicing

I require my students to spend a minimum of 30min/day practicing. I write down what I want them to practice and show them how I want them to work on those goals. My students diligently go home and try to do their best to work on their assignments, but sometimes I will have a student come back with little or no progress. Why? – They have failed to comprehend and apply the principle of playing vs. practicing.

Playing

- running a piece, movement or section of music with or without a specific goal in mind.

Practicing

- the act of approaching a piece, movement or section of music with a specific goal, a structured approach for progressing toward that goal, and a system for measuring progress on the goal.

Both playing and practicing need to be part of one’s practice routine, but we don’t call it practicing for nothing. Practicing needs to be goal oriented, structured and measurable if it is to be the most successful.

Goal Oriented

There are many different ways for teachers to make sure students are goal oriented in their practicing. For me, writing down in my students’ practice notebooks weekly goals for each piece of material they are working on works well. There are several reasons for this:

- It keeps the student organized. I don’t have students coming back after a week saying, “I didn’t know I was suppose to practice that!” or “I know you told me to change something in this section, but I forget what it was…” Students also have the beginning of a structured approach to their practice time. All they need to do is take the first thing written in their notebook and continue down the list until they have completed their material.

- It keeps me and the student accountable. Each week when a student comes back to lesson I focus in on the particular goals that I set for them, often going down the list of things in order. This system helps me remember specifically what I asked them to do. They also know exactly what I will be “testing” them on each lesson.

- For young students that have parents working with them who may or may not have had any musical training it gives the parent something to fall back on after the lesson instead of having to remember all the details of what I wanted them to work on with their child. It is also helpful for those students who have one parent coming to lessons, but maybe another parent working at home with the child. Having all the information recorded by me makes information transfer from one parent to another much easier.

The goals that are recorded in each student’s practice notebook are the things I expect to see progress on the next time they arrive. They are the things that need to be fixed, the WHAT of their practice time.

Structured

Practice time needs to be structured in order to make progress on goals. The structure of a practice session is the HOW. Without the HOW, the WHAT will probably not get accomplished. I often write the HOW in my student’s practice notebook as well.

For example: The WHAT might be to play 3rd finger D in tune. The HOW might be to stop on that note and check it with open D, listen for the ring of the note, make sure the 3rd finger is pushed down against the 2nd finger, etc.

The HOW of a student’s practice routine is often taken for granted by teachers. We expect students (especially older ones) to already know how to practice, but the truth is that unless students have learned this skill somewhere else, it’s a new skill that they need to learn just like they are learning a new instrument. We need to be just as diligent in teaching the HOW as the WHAT.

Measurable

Any kind of structure applied to practicing should be measurable, meaning that there should be a way of knowing on a daily basis how much progress was made on each goal. A lot of the time the structure has an inherent measurable component which makes it easy to track. Other times a measurable component must be applied externally. Here are some ways of measuring progress:

- section progress – track the number of measures you can play correctly on the first try

- tempo progress – track how fast you can play a passage correctly each day

- time progress – track how long you need to work on something before getting it correct

- repetition progress – increase the number of times you can do something correctly in a row

- memory progress – track how far you can get in a piece by memory

These are just a few of the ways progress can be measured during practicing. For students with a particular problem making measurable progress I often have them chart their progress on a daily basis in their practice notebook for me to see when they come back the following week. I have had great success with this. Once students have to actually write down their progress, they start making the necessary changes for progress to happen, and start to realize when their practicing is not being structured in a way that will allow for progress to occur.

Conclusion

For our students to be most successful we need to teach them the difference between playing and practicing, when to use each, and how to practice well. Goal oriented, structured, measurable practicing will result in a rewarding and successful learning experience for all. I hope this post will help you and your students get the most out of practicing!

Emily Williams is the creator of Strategic Strings: An Online Course for Violin and Viola Teachers

The Practicing Myth

What I call “the practicing myth” comes in various forms, but it always goes something like this:

“My kids hate to practice,

and I don’t want them to hate music, so taking music lessons must not be for them.”

If parents took that perspective with other things it might sound something like this:

“My kids hate eating vegetables,

and I don’t want them to dislike food, so healthy food must not be for them.”

“My kids hate doing their homework,

and I don’t want them to dislike learning, so school must not be for them.”

“My kids hate taking a bath,

and I don’t want them to dislike cleanliness, so washing must not be for them.”

“My kids hate cleaning their rooms,

and I don’t want them to dislike organization, so chores must not be for them.”

I think you get the picture.

Lets turn these scenarios around:

“My kids hate eating vegetables,

but I know it’s in their best interest to get the nutrition they need, so I will make sure they do it anyway.”

“My kids hate doing their homework,

but I know it’s in their best interest to get an education, so I will make sure they do it anyway.”

“My kids hate taking a bath,

but it’s in their best interest to be clean, so I will make sure they do it anyway.”

“My kids hate cleaning their rooms,

but it’s in their best interest to learn how to take care of their things and clean up after themselves, so I will make them do it anyway.”

Many parents enroll their children in music lessons because they realize there is value in music, not just as something to listen to, but as something to participate in. Many parents did not have the benefit of music lessons growing up and want their children to have an opportunity they missed out on. Some parents (like my own) took music lessons as a child, but did not stick with it and regretted quitting. Other parents see the value music lessons played in their own life and want their children to enjoy the same experience. I’ve also had parents enroll their child in lessons solely because the child had an interest in learning and the parent saw a benefit in giving the child the opportunity. Whatever the reason, parents enroll their child in lessons because they see a benefit to the child. But, somehow the focus changes when their child encounters an aspect to learning an instrument that they dislike. Usually this is the required daily practice. What if instead the parent had this perspective:

“My kids hates practicing, but it’s in their best interest to learn an instrument, so I will make them do it anyway!”

I’m up-front with parents who come to me discouraged because their child dislikes to practice. I tell them that I don’t expect their child to like to practice and that they shouldn’t expect them to either. There are rare cases where children are self-motivated to practice, and put in more than the required time and effort each day. Teachers and parents love these students! But, the reality experienced by most parents and children is that daily practice is a chore. Even if a child seems self-motivated at the start, the hard daily work it takes to learn an instrument can diminish their enthusiasm over the weeks, months or years. Parents see this and are afraid of pushing their child too hard, but, this is not a reason to give up on lessons. If we as teachers and parents truly believe that taking lessons on an instrument is beneficial to our students and children we should expect some dislike along the way, because hopefully we have learned for ourselves that most things that are worthwhile in life require effort and work, and are sometimes not fun.

When raised to eat healthy, do their HW, take baths and clean their rooms, children grow up to enjoy healthy foods, value education, practice good hygiene and are relatively organized adults. Music lessons and daily practicing can yield the same results. So, I encourage parents to approach practicing as they do anything that they know is good for their child, but that their child doesn’t like. Here are some good standards to follow to make practicing less of a battleground:

- Be Clear about Practicing Expectations: Set a practice duration, set clear goals of what’s suppose to happen during that time, and let it be known that arguing, whining or other attempts at thwarting practice time will have consequences.

- Set Consequences: Set consequences and follow through with them. Don’t make bigger threats than a behavior warrants or than you can follow through with. I have seen parents say, “I told you…..”, but they don’t ever enforce what they said. These children don’t last long in lessons.

- Give Rewards: Reward your child when they follow through with your expectations. A sticker chart, extra story time, a small piece of candy (like one Starburst), playing a short game, etc. are good motivators. Pick something that is particularly meaningful to your child!

- Set a Practice Time: When practicing is built into the schedule children will be more likely to do it without complaining. It will become part of their routine rather than an interruption to what they want to do.

- Make it Personal: Make an effort to give your child a special space for their studies. Personalizing their instrument, case, notebook, etc. can be a good motivator for practicing. This can be especially helpful if you have two children taking lesson. Getting them their own materials (not having to share) can go a long way to encouraging children to take ownership of their practicing and instrument.

- Eliminate Distractions: Make sure you and your child have a quiet place to practice. No TV, no interrupting siblings, no phone calls, no animals, no radio…whatever the source of distraction might be, eliminate it. This may require some cooperation from the rest of the family. Good! When the whole family supports a child in their music lessons the child will be more likely to succeed and see value in putting in the hard work.

While you want to avoid falling into the trap of “the practicing myth”, I am not suggesting that music lessons should be all drudgery either. I think it’s important that if your child does not like practicing that you find an outlet in music that they do enjoy. For me this was my weekly lesson and my school orchestra. For other students it may be time spent alone with their instrument apart from organized study, a chamber group, playing in church, or a music group of peers that get together to jam. Find out what makes your student or child enjoy their instrument and make sure that they are engaging in this activity on a regular basis in addition to their daily practicng. It will keep them motivated, and as they improve they will see the benefits that daily practice has for them!

Emily Williams is the creator of Strategic Strings: An Online Course for Violin and Viola Teachers

When and How to Teach Students to Tune

Tuning is the first thing we as musicians do before playing, so we should teach our students to do the same. Many teachers tune their students’ instrument for them, especially when teaching younger beginning students. While this may give more time in the lesson to teach other things, I think students are missing out on a very important skill and should be required to tune their own instrument right from the very first lesson. Tuning is part of playing an instrument and so we need to take lesson time to teach it. When taught efficiently, this skill does not have to take up too much lesson time.

All levels of students can learn to tune at the first lesson!

These are just a few of the important reasons students should tune their own instruments. You may have more to add to the list!

I generally teach tuning in three stages:

-

Tune the individual strings by plucking

-

Tune the individual strings by bowing

-

Tune the A-string, then tune the others to it in pairs by 5ths

With few exceptions beginning students of all ages can learn to tune their individual strings by plucking. I use a Korg TM-50 metronome/tuner to help my students learn to tune. I have them tune to the sounding pitch, then check themselves with the needle function. I find this particular tuner to be accurate, easy to use, and it produces all the notes in the correct octaves to tune the strings on both violins and violas.

Tuning is not necessarily an easy skill to learn, and if you attempt to have your beginning students tune all four of their strings in their lesson you can easily take up a full 30min!

To get the benefits of learning how to tune without taking up too much lesson time I have found the following methods to be effective:

-

Have students start by tuning just the A-string.

-

Put a 5min. time limit on tuning – see how many strings the student can get done in that amount of time.

-

Put a limit of 3 “checks” per string on tuning. This encourages students to more diligently use their ears!

-

Give a sticker for every string tuned correctly in the given time limit.

-

Have the student verbalize if their string is “too high”, “too low” or “just right” before turning the fine tuner. This keeps the student engaged in the process and helps you know what they may or may not be hearing.

-

Have the student hum the the pitch of their string, then the correct pitch. Have them identify if they needed to go up or down in their voice to get to the correct pitch. Sometimes the physical sensation of feeling what their vocal chords need to do is helpful. (This process even works for students how have trouble vocally matching pitch!)

Once a student has successfully learned how to tune the individual strings by plucking they are ready to tune using the bow. Make sure that your student has also learned how to produce even long tones with their bow before attempting this step. A poor or inconsistent tone will change the sounding pitch of the string and make it difficult for students to hear the correct pitch.

At this stage it is also important to make sure that the student is turning their fine tuners only when their bow is moving on the string. Most students will attempt to play their string, stop the bow to turn the fine tuner, then bow again to check where they are. It is much more effective to have the student turning the fine tuners with their left hand while bowing with the right. It will be awkward at first, but a student will be able to match pitch much more easily this way.

Encourage students at all stages to go slightly above and slightly below the in-tune pitch to help them learn how to find the center of the pitch. Going back and forth like this helps them hone in on where in-tune is.

Lastly, students are ready to tune their strings in 5ths when they can easily tune their individual strings with their bow. I also recommend that you introduce double-stop playing into a student’s repertoire before attempting to teach this tuning step. Tuning strings in 5ths is very similar to tuning double-stops. The student who has trained their ear to hear double-stops and adjust their fingers appropriately will most likely find tuning in 5ths not too difficult.

When introducing this last stage of tuning I normally show the student on my violin what to listen for. I describe it as listening for the strings to produce a 3rd note. This overtone sometimes sounds like a low rumble. It will become louder as the 5ths are more in tune. Once a student understands what to listen for they can try it themselves with their instrument.

When approaching tuning in these three stages and in the ways described I have found that students of all levels successfully learn to tune, and that the process positively influences how they approach tuning the notes of the left hand as well because their ear is being trained to recognize small nuances in pitch from the start!

Emily Williams is the creator of Strategic Strings: An Online Course for Violin and Viola Teachers

Teaching Vibrato: A Guide for Teachers

There are a variety of ways to teach violin vibrato as well as several different types of vibrato. The arm vibrato and the wrist vibrato are the two most common forms of vibrato. I teach an arm vibrato. Some argue that an arm vibrato is not as versatile as a wrist vibrato, but I have seen violinists of all calibers who use it, sometimes exclusively. In my opinion you can get a lovely vibrato using either form as long as you are taught how to use it properly and effectively.

Let’s start out with what a vibrato is NOT:

- A vibrato is not a “wiggling” or “shaking” of the hand, finger, arm or wrist

- A vibrato is not a sliding of the finger on the string between two pitches

- A vibrato is not an uncontrolled spasm of the hand

- A vibrato is not created by tensing the muscles of the arm, hand or wrist

Learning the arm vibrato starts with an understanding of how the finger, hand, wrist and arm work in tandem to create the vibrato. I usually teach students vibrato shortly after they learn 3rd position for two reasons:

1) By this point they should have a good understanding of the basics and be ready to add a new technical element into their playing.

2) The hand in 3rd position hits up against the body of the instrument, creating a natural starting and ending point to each oscillation of the hand.

Have your student start with their 1st finger on the D on the A-string. Their wrist and thumb should be straight and the edge of their hand should be resting against the body of the instrument. All fingers should be curved over the fingerboard.

Beginning with the arm the student slowly moves the arm back, the wrist stays straight and the hand follows requiring both joints on the finger to open (the finger elongates). The side of the index finger slides along the edge of the fingerboard. If done properly there should be a ½ step change in pitch (D to Db). This is created by the fact that the finger is actually “laying back” on the string. Both joints should open, but neither should collapse. The student should then bring the arm, hand and finger back to the starting position, keeping the wrist straight.

Note: A proper vibrato goes below the pitch only, not above it. You start and end on the “in tune” pitch.

The student should hone this skill until they can do it comfortably keeping their hand position correct. Make sure that the student’s fingers (all of them) are relaxed.

The next step is to do several oscillations in a row at this slow tempo. The bow changes as needed.

Once a student can do this step confidently you will add a metronome to the exercise. Put the metronome on a tempo where they can move their hand forward and back (D to Db), each on a click, keeping the hand movement correct.

Speed this up as the student masters the tempo. Think in rhythms. Have the student do quarter note oscillations (D, Db, D, Db), then 8th note, then triplet 8ths, then 16th notes, etc. Feel free to change the metronome speed as needed to accommodate the student. Perhaps the metronome is on 60 for the quarter note oscillations, but on 50 for the 8th note oscillations. That’s fine. The objective is to incrementally increase the tempo at a rate that the student can keep their hand position correct. Soon they will be at a tempo that could be considered a “working vibrato”.

At this point you can tweak and hone the vibrato so the two pitches are not so clearly distinct. This will create the warmth that we are looking for in vibrato.

This process takes a different amount of time for each student. Some students learn it in a matter of weeks, some take a year or more. Remember that it’s not how fast the student learns the technique that’s important, but how accurately they learn the technique. You can also use this technique for students that already know vibrato, but have been taught in such a way that they have a tight spastic vibrato, or only have one speed of vibrato. This technique teaches students how to control their vibrato at every level.

Emily Williams is the creator of Strategic Strings: An Online Course for Violin and Viola Teachers

To learn by ear or by reading music: That is the question…

With the introduction of the Suzuki method in the United States came an increase awareness and division between those who learn music by ear and those who learn by reading music. For those unfamiliar with the Suzuki method please read my following post outlining its basic tenants, history and success in the US: http://blog.playviolinmusic.com/2011/01/17/experiencing-the-suzuki-method/.

Since this time many debates have ensued about whether students should be taught to read music first, or whether they should learn by ear first and learn to read music later. If you read my aforementioned post on the Suzuki method you will know I am not an advocate of the method as it has been employed in the US. I believe in teaching students how to read music from the first lesson. However, this does not mean that I think students should not also be taught how to play by ear. I think that it is important for students to acquire both skills.

Proponents of teaching students to play by ear usually quote from Suzuki who promoted the idea that young children should learn music just as they learn language. He postured that since children learn to speak before learning to read, music should also be approached from this same premise. There is truth to this idea, however the problem comes in its implementation.

When do we expose children to speech on a regular basis and when do children start imitating speech? They are exposed to speech from the womb and begin imitating what they hear before they can even walk. Children begin to speak words and form sentences far before the age of 2. When do children normally start music lessons? Age 5, 8, or 10? If we are going to teach children music the same way they learn speech, the time for learning by ear needs to come far earlier than when most students begin musical instruction. Many Japanese students of Suzuki did follow this musical training model. Music was a family affair which included daily classical music listening and practice. Babies born into these families demonstrated recognition of music that had been played for them while they were still in the womb. Their musical training had already begun.

Most students in the US will not have this experience, and that’s OK. Children can still learn music and an instrument and become well trained musicians. In order for this to happen both ear training and music reading must be part of a student’s lesson experience. I start with music reading so that students can begin to make the connection between what they see on the page and what they are playing on their instrument. If students do not have this training they are more likely to have trouble making this connection later one.

Students are also encouraged to listen carefully to what they are playing. String instruments require students to acquire a very good ear if they are to play their instrument well. This type of ear training should occur from the very first lesson. As a student progresses and gains a good understanding and functionality on their instrument I introduce how to play by ear. This will happen at different stages for each student. Just as we start teaching children the foundation of reading words by teaching them their letters as soon as they are able, so should we introduce students to the foundations of music reading as soon as they are able to comprehend it. As we combine this with the training of their ear they will be more complete and competent musicians at every level.

Emily Williams is the creator of Strategic Strings: An Online Course for Violin and Viola Teachers

Studio Recitals and Teacher Performance

Studio Recitals are a wonderful opportunity for students to showcase for family and friends all the hard work they have done. It’s also a great benchmark for students to work toward and a time for them to realize how far they have come since their last performance.

I recently got asked by a parent if I had ever thought about performing for my students at one of these recitals. The short answer is ‘yes’ I have thought about it and, ‘no’ I have chosen not to perform. Let me first say that I think it’s important (I would even go so far as to say imperative) that students see their teacher perform. That said, I have chosen not to make my Studio Recitals a venue for this to happen for several reasons.

The first reason I choose not to perform on Studio Recitals, and perhaps the most important one, is because I believe it’s important for students to hear me play out in the “real world”.

Students need to attend professional concerts in order to gain an understanding of what it means to be a musician. Fostering an appreciation for professional concerts contributes to the education of young musicians. Whether a student chooses to become a professional musician, amateur musician or a musical spectator they will need this education. There is becoming a widespread ignorance of classical music as a profession and as entertainment because children are not educated and exposed to it, therefore as adults they do not understand or value it. It is my desire to encourage parents to bring their children to professional concerts of all kinds. Students and parents who are interested in hearing me play can attend a local symphony concert, a solo recital, a chamber performance or a special church service. I make it easy for parents and students to know when these opportunities are taking place, and many performances are free. I believe the value for a student in hearing their teacher play lies not only in the experience itself, but also in the venue and atmosphere in which it takes place.

The second reason I choose not to perform on Studio Recitals is a personal one: it’s simply too busy and stressful for me to plan a recital for all my students and perform on that same recital.

As one who knows what it’s like to experience severe performance anxiety, I have learned in my professional career what I must do to cope with this. (You can read about some of my methods on the following post: http://blog.playviolinmusic.com/2011/07/26/performance-anxiety/ ) I believe any teacher/performer will tell you that while teaching and performing are intrinsically related, they are very different functions for the individual. When I perform I need to be in a different “mode” or “zone” than when I am teaching. In order to do my job well I need my mental and physical energies to be dedicated to that task. Probably no one but my husband knows the time and effort that goes into coordinating each Studio Recital, and for me, performing even a “simple” piece would add too much undo pressure and would take away from my ability to be fully dedicated and available for my students.

The third and last reason I choose not to perform on Studio Recitals is because I do not want to take away from the work of my students.

Studio Recitals are a special occasion, set aside to celebrate the work of my students and I desire this to be the focus of each Studio Recital program. My goal is to have students leave with a sense of personal accomplishment, not a feeling that they have “so far to go” to get to the level of their teacher. This said, I do perform with my students on duets or in other capacities that serve to highlight and support my student’s music. I believe this is important and very appropriate. Studio Recitals are a day for my students and I desire to keep them that way!

Emily Williams is the creator of Strategic Strings: An Online Course for Violin and Viola Teachers

Questions to ask Prospective Teachers

When it comes to choosing a teacher for yourself or your child you want to make sure the teacher you choose will give you quality instruction. Teaching philosophies, techniques and goals will greatly impact what kind of instruction each teacher gives. It can be an overwhelming task to pick a teacher, especially if you don’t feel qualified to critique in this area – however, it’s imperative that you do! Even if you are unfamiliar with music you can gain insight and knowledge just by asking questions. Ask the same questions to a few different teachers. Teachers are usually very happy to talk about their teaching philosophies!

Here is a helpful list of questions, designated by category, that you can ask a prospective teacher in order to evaluate their teaching style.

Experience

- What is your professional and educational background in music?

- What is your teaching experience?

Studio/Policies

- Where do you teach/What is the atmosphere of your teaching environment?

- What age groups do you teach?

- Do you have a written studio policy?

- What is your cancellation/rescheduling policy?

Requirements

- How much practicing do you require from your students?

- What role do you expect parents to play in their child’s practicing?

- What do you expect from weekly practicing?

- Do you require students to learn scales and etudes?

- What are your requirements for students to progress from song to song?

Materials

- What books or materials do your students use?

- What kinds of music do you teach?

- What materials/accessories other than an instrument do you require your students to purchase?

Teaching Philosophy

- What emphasis do you put on correct technique?

- How do you evaluate student progress?

- In your opinion, what’s the most important thing students should gain from taking lessons?

Performance Opportunities

- Do you offer Studio Recitals? Are they required?

- What festivals or competitions are available for your students?

- Other performance opportunities?

Fees

- What are your lesson fees?

- Are there any extra fees other than lesson fees?

- When/how are lesson fees paid?

You do not need to ask every question on this list, but do choose at least one from each category so that you get a broad overview of a teacher’s style. You may also have questions of your own to add! Remember, no question is stupid. Teachers do not expect that you know everything (or anything) about music and are more than happy to answer any question you might have for them!

Emily Williams is the creator of Strategic Strings: An Online Course for Violin and Viola Teachers